The landscape of bio-medical research in the UK is changing. The growth of digitisation, workforce agility and a push towards a more collaborative and inter-disciplinary approach, requires a re-think of how design should nurture the growth of this sector. AKT II director Rob Partridge, who led the structural and civil engineering design on the Francis Crick Institute, talks on the importance of providing the UK’s life sciences market with the fabric and infrastructure it so desperately requires.

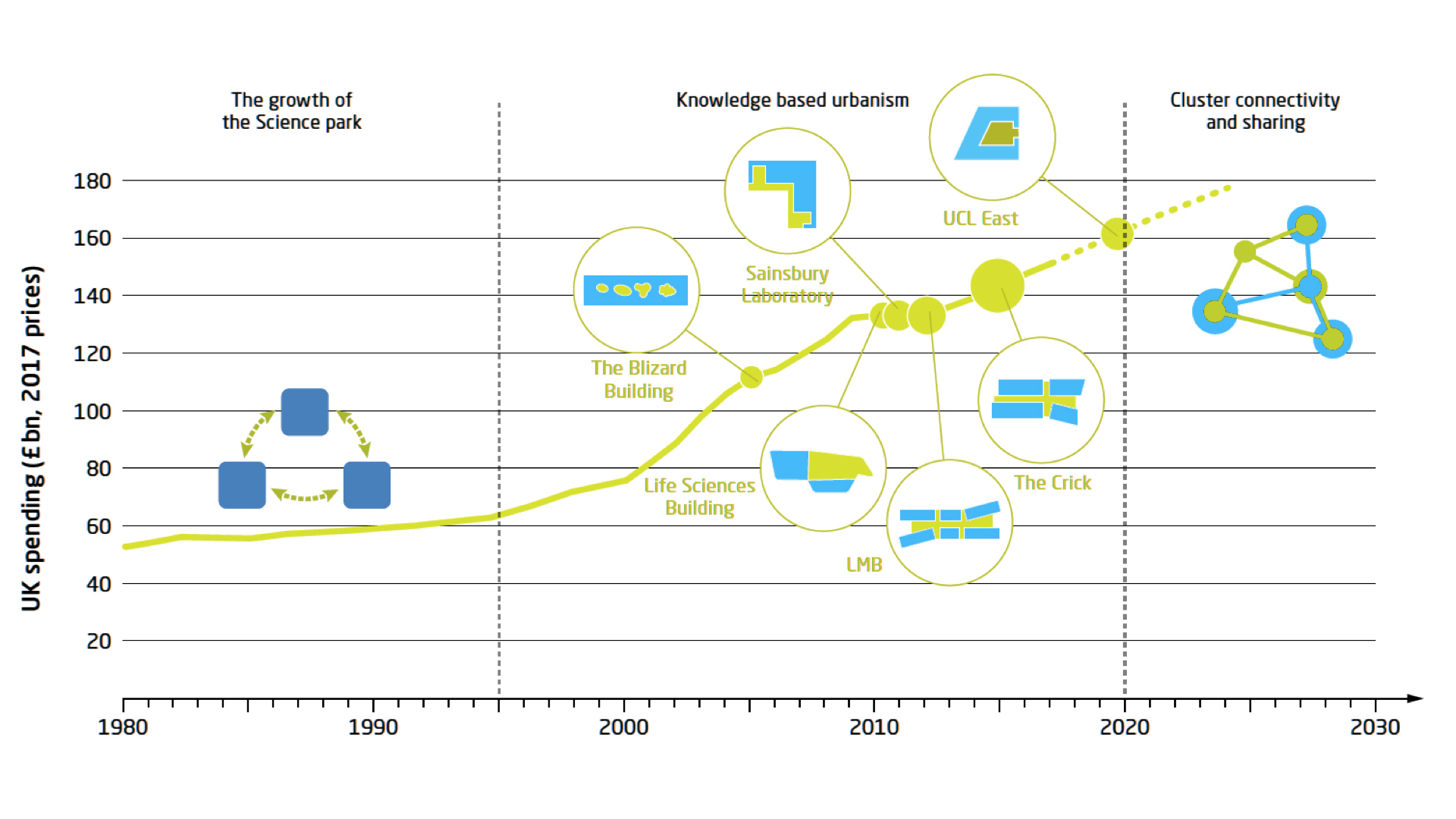

Over the last 20 years, there has been tremendous growth in the life science industry worldwide driven by demographic shifts and continuing advances in biomedical research and production. The UK boasts an impressive history of scientific discoveries but has traditionally lacked the ‘translational’ infrastructure to turn research into business, thus losing our intelligence overseas and resulting in missed economic opportunities. To correct this, the sector has been seen as a key growth area by the UK government and continues to attract cross-party support and funding.

This move to translational research is coupled with a trend towards the urbanisation of science. Science parks traditionally provided the UK’s home of research, driven by urban planning ideologies of the latter half of the 20th century. Partnerships between government and large pharmaceutical companies provided clusters which tended to be characterised with an inward-looking and protective environment. However, at the same time, cities have been forming ‘knowledge clusters’; eco-systems of academia, research and incubation woven into the urban fabric of our cities. These innovation districts are continuing to expand, and new ones are forming, increasing the pull of life science into an integrated urban environment; and exemplified by the building of the Francis Crick Institute in King’s Cross which opened in 2016.

The brief of the institute was to bring together six of the country’s leading academic and research institutions under one roof – to create a space and a volume that would nurture collaboration between these different disciplines, and break down metaphorical barriers between them.

The Francis Crick Institute was designed with flexibility in mind, a set aspect of the brief. As the largest laboratory in Europe, spanning 1 million ft² in central London, it sets a precedent for future buildings within the life sciences industry. As no one will be able to predict the likely evolution what the future of research looks like and how it is carried out, it was essential that a level of future-proofing was built into the backbone of the building.

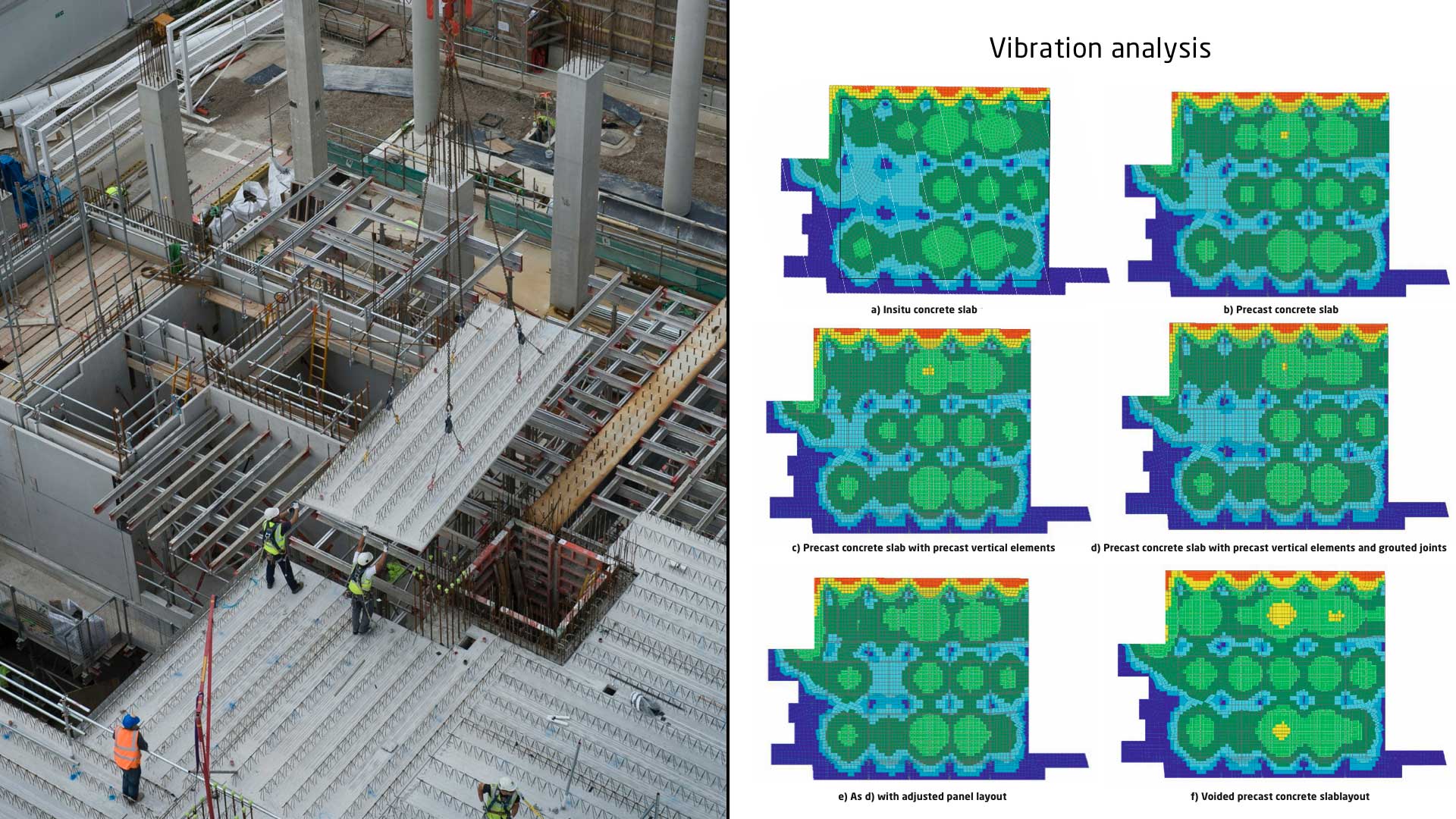

A key design driver in the Crick, and in all laboratories, is vibration. The team at AKT II carried out meticulous assessments in the early days of design, to effectively look at the implications on the cost of the structure, should we design the whole institute for a particular specification. As such, all the floors are designed to a defined vibration specification, providing inherent flexibility over the whole span of this development. This was compensated with a stiffer, heavier and thus more costly structural design, but it provided the Francis Crick Institute with the required future flexibility that the life sciences market requires.

This unique research was continued through the use of prefabricated systems with a forensic evaluation of the effects of joint detailing on the response of the floors. This research enabled the obvious benefits of off-site manufacturing, in terms of logistics, quality control and programme to be realised, as well as exploiting the quality of the concrete finish which was exposed in some areas, giving the future occupants a rare glimpse of the structural backbone to the institute.

Two years since the completion of this project, the evolution of life sciences into the urban environment is continuing. One of the key factors going forward is to provide a space for the ‘birth’ of startups – already being formed from the initial success of the Crick. Small start-up companies need an incubation space, an environment that is designed as such that they can rent a small space but have access to all the required support functions with a building that is designed to an appropriate lab specification. This provides small companies with the facilities to scale up to a larger practice and eventually continue to grow and begin production in the UK. The transition from the birth to the production for these companies is a key element which we must provide.

Referencing the frequently defined golden triangle (Oxford – Cambridge – London), there is a real need for London to provide these incubation facilities that can match the current scale and targeted growth of the sector. Compared to its neighbours Oxford and Cambridge, London needs to begin creating spaces that are fit for start-up bio-medical companies, but that are flexible and adaptable enough to accommodate future users.

The question posed is: how do we provide that? A space that can accommodate start-ups whilst still providing the facilities required. This is where we look to the modern office.

Closely interlinked to life sciences, we are also witnessing massive changes in the way we work that is also changing the landscape of the modern office. As a result, workplace design is now being driven far more by the needs of users and the erosion of traditional working practices and disciplines is driving a focus on collaboration, adaptability and flexibility – inherently similar to the fundamental of lab design.

Our home, the White Collar Factory, is an exemplar of the evolving workplace typology, where the building is created using a low-cost, loose-fit model, providing a flexible volume to accommodate future workers’ needs. The whole design, including the specifications, floor-to-ceiling height and the geometry of the building is driven by the need to create adaptable space that is already home to an eclectic mix of tenants and which can begin to serve the merging of industries from maker space to life sciences.

Creating a space that nurtures collaboration is also becoming extremely important, and thus the workplace is learning from the success of teaching and research institutions. In the life sciences sector, environments are designed to promote interaction and create serendipity, which has been proven to increase both the breadth and likelihood of scientific breakthroughs. Derwent London’s activated and adaptable lobby and Bloomberg’s sixth-floor entry point and ramp access are modern-day examples of the convergence of workplace and life science sectors.

These workplace trends are also being embraced by tech giants such as Google and Facebook, whose evolving briefs are underpinned by a need to design volumes which can ‘enable’ invention and research. With the convergence of disciplines and working practices driven by digitisation of data, the obvious link to life sciences is already being seen, and thus we need to address this need in our commercial workplace design.

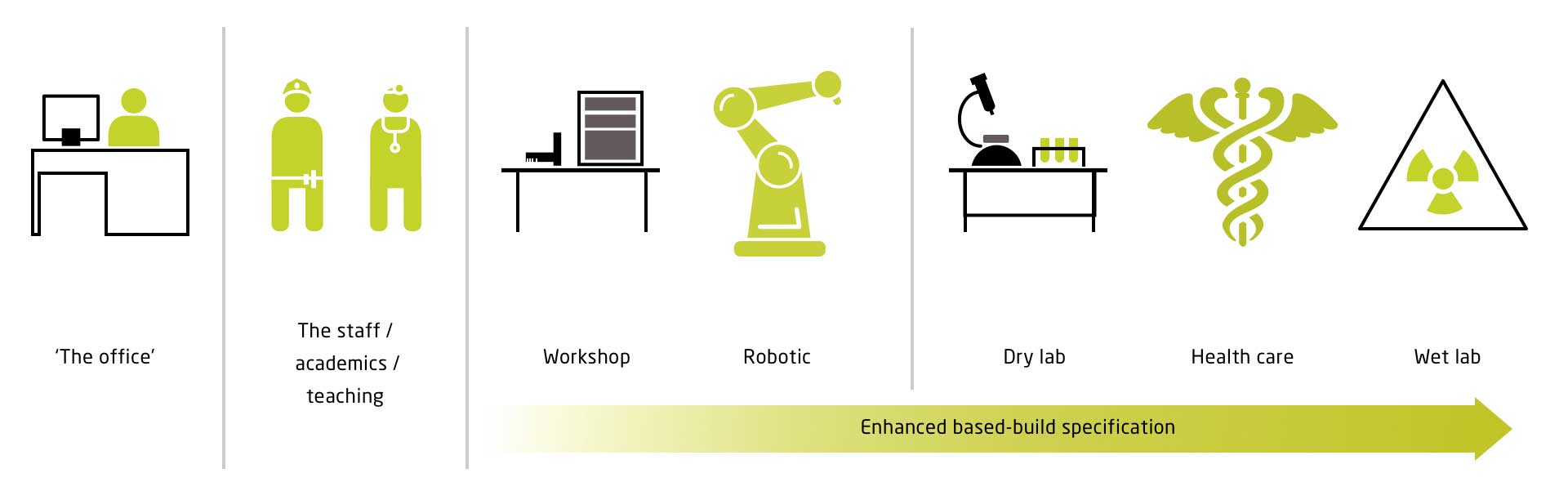

Thus, there is now a need to study in detail how we might design workplaces which can enable life sciences and biomedical research in the future – without providing the full-scale specification of the Francis Crick Institute. The freedom that is provided across all floors of the Crick is not economically realistic or necessary for the current needs of the UK market. The solution is to find a middle ground between what is an appropriate specification and, therefore, what is an appropriate level of adaptability – one that entices and provides environments for start-ups as well as more established companies.

There are a few key factors involved in this design:

Exploring in-depth what the specification for these spaces should be, and instead of designing for blanket specifications, we look at the forensics of all the different scientific functions that may exist across a floor – looking at the minimum and optimum criteria, weighed up against where you might provide those spaces across the floor plates. By being ‘intelligent’ with floor use, we can drive the design to meet different specifications in different areas.

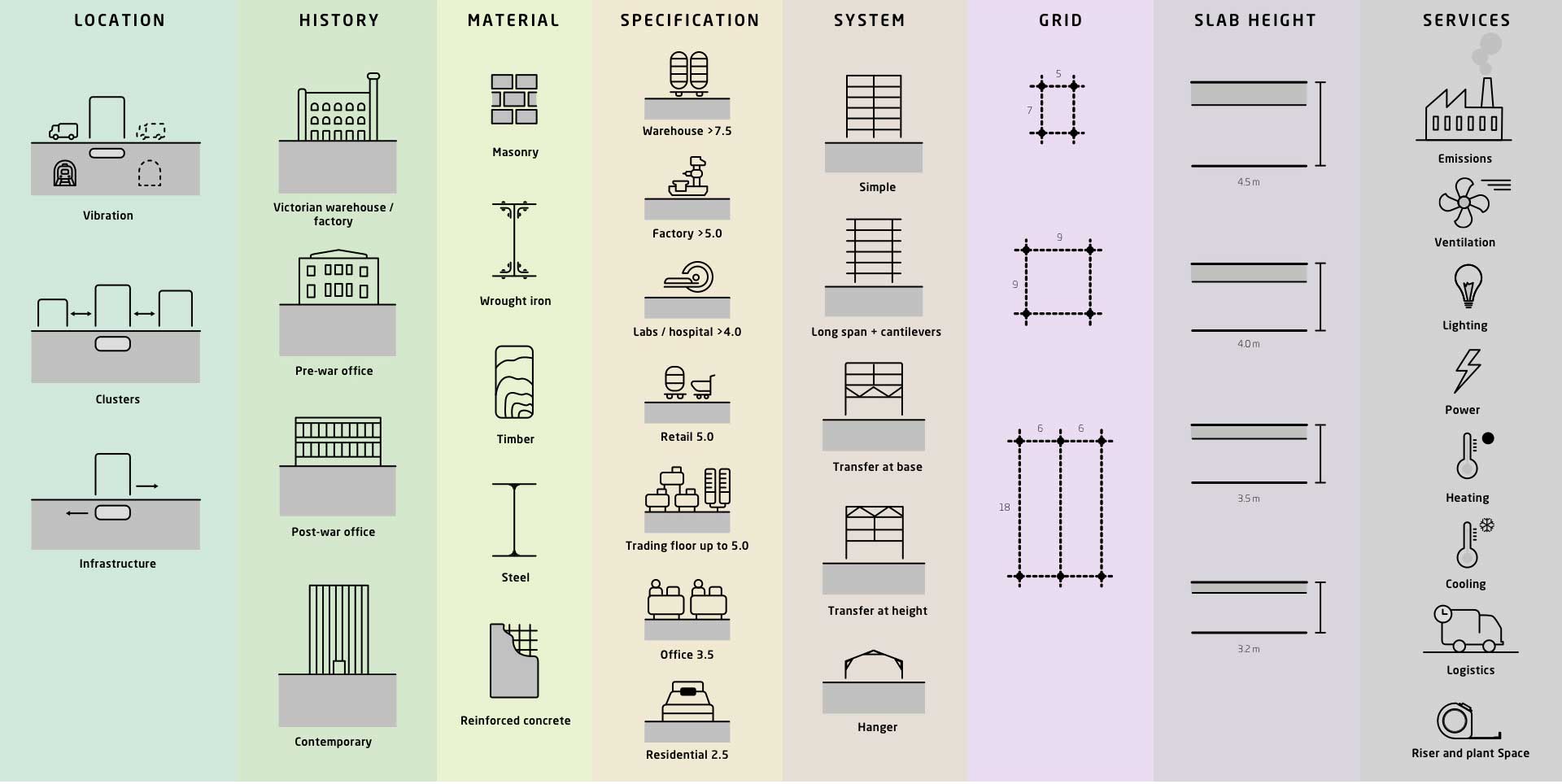

It’s crucial to think about the location of the developments housing life sciences, relating to connectivity to existing knowledge networks. Currently, there are defined ‘clusters’ in London, as well as within the ‘golden triangle’ including Oxford and Cambridge. On a more local scale, the focus turns to the proximity to sources of vibration, which would affect the behaviour of the building. A move to shared facilities, used by a variety of different plots can help here, by removing stringent criteria from all but one part of a cluster.

In the same way that the industries we design for is experiencing unprecedented change due to digital and technological advancements, engineering design itself as a discipline has also benefited. We can now harness the computational power available and provide optimum solutions to hugely complex data sets. Combined with a greater understanding of the science of materials we build with we are able to predict engineering performance with far greater levels of certainty.

One thing we’re proud of here at AKT II is the fact we are able to reuse existing structures as opposed to solely focusing on new-build developments, which interlinks into the debate around future-proofing and adaptability. Within the life sciences sector, this can complicate things. There are many variables that must be evaluated to conclude the appropriateness of a particular building, including age and construction, internal geometry, servicing and of course location.

Driven by environmental, demographic and socio-economic trends, how we will ‘use’ the workplace in the future is becoming a very real debate in design. This is of course driven by the evolving definition of ‘work’ as crossovers begin to emerge between traditional siloed sectors. With the growth of life sciences predicted to accelerate combined with the current thinking into adaptable typologies for the growing tech clusters, an integrated approach to the design of life science-enabled workplaces is imperative.

This proposition transcends scale from floor-by-floor adaption to whole building future-proofing, and to contextual planning on an urban scale. As designers, planners and policymakers we have the ability to weave life science into our urban fabric, creating a robust foundation for the future growth of this vital sector.